Travels with Marwan: Return to Uganda, Part 2

Week 2: Days 1-3

It is incredible how incapacitating it is when there is no access to internet. I will confess that I am of the generation that grew up and went through college without internet. And I honestly do not remember how that worked. It obviously did but being without it today disconnects you from family, friends, colleagues, society, work; in a word, from the world. I have been able to speak to my children only a handful of times so far. I have been able to answer an insignificant number of emails and only on my phone. I have not been able to log into work and I worry that my team is overburdened with many extra hours covering me and that a disaster or two are brewing, disasters that could likely be avoided if only I had internet (of course, I know that my team back in the U.S. looking after my patients are truly remarkable and can handle anything that comes their way—it is just hard not to worry). I am completely out of touch with what movies are in the theaters, what the latest songs are playing on the radio, and what has been happening politically in these contentious times. And as infuriating as all that is, I realized that for most of the colleagues we are working with here in Nebbi, this is their reality. Internet access is a luxury in this rural district, definitely not the norm.

And it is in this reality that we are going to attempt to stay connected with the clinical teams over the next year. We have been testing the connectivity at each site. Signing up anyone who has a smart phone (again, the exception, not the norm) to WhatsApp—the platform where we hope our conversations and discussions and teachings and sharing will continue long after we have left Uganda and are back in the U.S. at our respective health centers. We were testing the bandwidth to see if Zoom can be accessed on site. Most of the time, it was not possible. But solutions were being discussed. Perhaps people can be brought to one site that does have internet access and they all can join from there every 2 weeks.

We brought Mifis with us from Kampala (small devices you had to sell your first born it seems to get—well, it was more like you had to register, give your passport, you were limited to only one device, etc., but you get the idea), hoping that having these hotspots would make a difference. Unfortunately, most of the time, it didn’t. Yet, it was encouraging to know that there is now a huge focus from the health centers, the partners supporting the districts, and most importantly, MOH on ensuring access will occur. Soon.

Our site visits continued. Each day, starting at the crack of dawn, we would meet briefly at the modest buffet for a cup of coffee, delicious pineapple, and a piece of bread or pastry—for those much more adventurous than I, they would choose to eat the hot local food which to me looked suitable for dinner but not breakfast. I have a very specific idea of what breakfast should be that limits me, happily, to eggs, waffles, pancakes, toast, bagels, pastries, fruit, you catch my drift. I am sure I am missing out but at this point in my life, I am okay with that.

For dinners, I did venture out a bit more given that we ate at the only restaurant at our hotel every evening and the menu never changed. Surprisingly to me, Indian cuisine is quite prominent here in Uganda. So, I did indulge in biryanis and curries, granted a little less often than the grilled cheese sandwich and the mouth-watering tilapia.

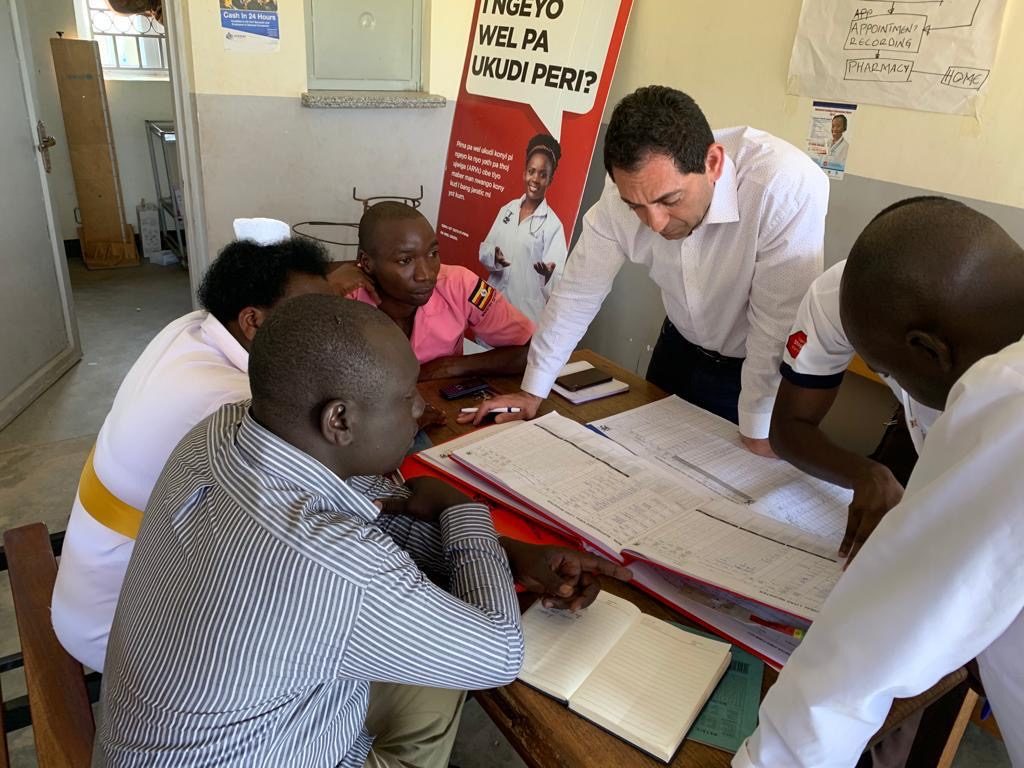

We would get into our car right after breakfast and we would head out to the scheduled health center for the day. We had the ability to get to one site each day and to spend only a few hours there given the distances we had to travel. Nevertheless, that seemed to be enough time to catch up with our wonderful colleagues and have a great discussion about the services being offered and what they thought needed to be improved and what has worked in the last 6 months. Uganda has embarked on an impressive national quality improvement initiative targeting viral load suppression rates with projects focusing on interventions to reach the 95-95-95 goals—diagnosing 95% of all people living with HIV, treating 95% of those diagnosed, and achieving 95% viral load suppression among those on therapy. To put that in perspective, we in the U.S. have diagnosed 85% of people living with HIV and have about 50% of people in care and virally suppressed. The Skills Sharing Project has corresponded really well with the timing of the Ugandan national initiative and truly complemented the work that was being done. All this to say, it is hard to draw a direct line between our May visit and the successes we have witnessed. Regardless, it has been really amazing to see the progress and to see many of the discussions and suggestions that were made in May come to fruition in a short 6 months.

Whether it was at Nebbi Hospital or Angal St. Luke Hospital, or Nyaravur Health Center—the three sites we visited these past three days, the challenges seemed to be similar, as expected. Stigma and a stretched workforce resonated across the district. Yet, the foundations of team-based care, case management principles, data driven interventions, and enhanced clinical support have all been laid. What we were providing now is the encouragement to build upon these foundations. And frankly, these are the same foundations we need to build upon in the U.S. as we gear up to end the HIV epidemic by 2030.

Our site visits culminated with bringing all the health center sites from the three districts the Skills Sharing Project was in (Nebbi, Jinja, and Kayunga) together with the MOH for a virtual Zoom session where presenters from every district shared their successful initiatives. It was truly magical to see all the participants listening to each other, becoming inspired by the great work their colleagues were doing, and realizing the power of this virtual platform for sharing and learning. It felt like this was a true turning point in what the MOH wanted to establish and what this Project was trying to do.

As we bid farewell to our friends and colleagues, there was a sadness in the air, knowing that this might be the last time we may be here in this capacity. The idea is that, moving forward, we would be connecting only virtually. As we hugged goodbye, no one wanted to acknowledge it. We kept saying ‘see you soon… perhaps’.

I felt that we needed at least one more visit to solidify all the work that has begun to date. That also may be my desire of not wanting this to be the last time we all saw each other.

Week 2: Days 4-5 and Departure

The time to depart has arrived. And we were sad. As excited as we were about the prospects of seeing our families again, we were awash in melancholy, knowing this may be the last time. In May, we knew we had one more visit. This time, we don’t.

We woke up a bit earlier than usual to get on the road as quickly as possible for our 8 hour drive back to Kampala. And we were unusually quiet in the car at first. That may have been because it was early and we were exhausted. Either way, we were all lost in reflection for a while.

Looking out the window, I was seeing the hustle and bustle of life whiz by. Seeing women walking with baskets and goods on their heads, I continued to be so amazed at the skill with which they are able to do this, with postures enviable the world over. I was seeing individuals working in the fields on small plots of land that may be their own or rented from people more fortunate than them. I was seeing the market places by the sides of the road start to fill up. I was seeing kids of varying ages dressed in uniforms with colors specific to the schools they were attending—the bright purples, greens, yellows, reds, blues. I saw a graduation procession for what looked like 6 or 7 year olds marching down the road. I was also seeing other kids not in uniforms, knowing that their families could not afford the fees or the uniforms to send them to school. I could not help but wonder, having interacted with kids in the health centers and seeing them on the street, how resilient all of them were. How the older brothers and sisters would be looking after the younger ones, holding their hands as they walked, sometimes carrying them. Seeing the bonds of siblings form so young. Seeing kids on the streets trying to sell goods. Negotiate for food. Play with makeshift toys out of scraps of wood. Happy, laughing, dancing, playing. And I just could not help but think: What if these kids were born under different circumstances? Is there an Einstein among them we will never see their potential? A Beyonce? A Picasso? A Toni Morrison? A Maya Angelou? A Nelson Mandela? A Michael Jordan? How many kids will never see their potential because of the circumstances they were born into? And this of course brought me back to the U.S. and the communities we work in. I constantly think about the potential of the children we see in our health centers and worry that it is the rare child that is able to rise above their circumstances and shine bright, when I know there are so many children waiting to shine if they are given the chance in life.

In pulling into the city of Bweyale, the main road running through it was wider than usual with huge markets on both sides of the street filled with people. It turned out that nearby was a large refugee camp filled with people from South Sudan, Congo, and Ethiopia. Right in the middle of the market stood a huge billboard—on the one side was an advertisement about fighting corruption in Uganda and on the other side was the logo ‘Citizens Have a Right to Proper Healthcare’. And once again, the similarities were glaring—the words on the billboard were loudly reminiscent of our motto at CHC (‘Healthcare is a Right, Not a Privilege’) and of the fight we constantly are having in the U.S about healthcare.

There was definitely a doleful mood in the car, knowing the possibility that this could be the last time we drive this route, last time we work together, last time we visit the sites we have established these bonds with.

Upon arriving at the Hotel Serena, we were tired by the long drive. We pushed through dinner since we knew we had to finish up and submit our summary slides of our visits for presentation to PEPFAR and to MOH tomorrow. We had a meeting that evening to run through what turned out to be an extremely tight presentation time. Nevertheless, the debriefs with the U.S. and Ugandan higher-ups went extremely well the next day. No one broached the subject of a return visit but there was much talk about continued virtual support and sustainability.

That final evening, the majority of us were on the same flight from Entebbe to Amsterdam. So, we kept delaying our farewells. But we finally had to face the reality that this adventure was over as we all hugged goodbye and went off to our separate gates. We promised to stay in touch. We knew we would see each other on Zoom, at least for the next year.

To know that each and every one of my U.S. colleagues is flying back to a different part of the U.S. and that they will all play an integral role in ending the HIV epidemic, I knew that our fight in the U.S. is in very solid, very good hands. We all saw the potential of our Ugandan colleagues achieving the lofty goals of 95-95-95 and we hoped that our interactions and the sharing of knowledge and skills and challenges would play a small part in moving both Uganda and the U.S. forward in the quest to halt new HIV transmissions, to prolong the lives of those living with HIV and improve their quality of life, and to truly end this decades-old epidemic that has stolen generations of human potential from the world.

So, here’s to the Global End to the HIV Epidemic, country by country, community by community, individual by individual. Here’s to a World Without AIDS.